Interview by site editor Dan Chung:

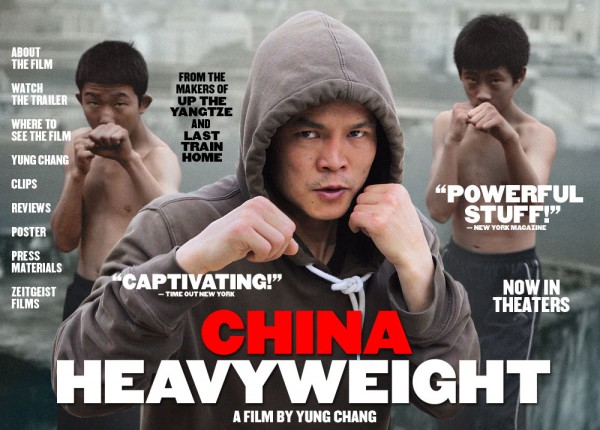

China Heavyweight is one of the most successful Chinese feature length documentary films in recent years. A co-production between Canada’s Eyesteel films and China’s Yuanfang Media, it tells the story of a boxing trainer in rural China who re-enters the ring to represent his country. It has won numerous awards and is currently on cinema release in mainland China. Showing on more than 200 screens nationwide it will be the most widely theatrically screened documentary in Chinese history.

Shot mostly on a Canon 5D mkII it is one of several documentaries now entering theatres that were shot during the early days of the DSLR revolution. I spoke to Director of photography Sun Shaoguang and producer Han Yi about the challenges. Shaoguang has been a director of photography for about 14 years, having studied photography at college and then worked at a TV station before starting to work on documentaries in 2005. Han Yi has been producing documentaries for seven years and now runs her own Beijing based documentary production company.

China Heavyweight – Trailer from EyeSteelFilm Distribution on Vimeo.

Q Can you tell us a bit about China Heavyweight?

A [Han Yi] China Heavyweight is not just a boxing film, but a film about respect, honor and perseverance – virtues at their greatest test in a changing China. We followed a coach who recruits poor rural teenagers and turns them into Western-style boxing champions. Through hard work and discipline, these boys and girls come of age, trained in the art of boxing and the game of life. They are filled with Olympic dreams, hoping to become China’s next amateur heroes. Their coach hopes to make a storied comeback in a final pro fight, to show them the way. The top student boxers face dramatic choices as they graduate – should they fight for the collective good as amateurs or for themselves and their own personal gain as professionals. It’s a metaphor for the choices that everyone faces now, in the New China.

We premiered at Sundance, screened at Hotdocs in Toronto and then went on to win the best doc at the prestigious Taiwan Golden Horse awards. It just went on general release across China.

Q Who chose to use the 5D?

A [Shaoguang] China Heavyweight has a different style to [our last documentary] Last Train Home. It wasn’t me who made the decision to use the 5D, but the director – I actually didn’t really like the 5D at the time because a stills camera felt too different from a video camera.

If it had been up to me I would have used the 7D, but the 7D doesn’t have as many lens choices. At that time the 5D had just come out and the director wanted to give it a try. I think we were the first group in China at that time to use the 5D – now it’s common. We started shooting in 2009 and finished in 2011.

Q Had you seen documentary work on the 5D?

A [Shaoguang] As a cameraman interested in equipment, of course I knew about the 5D. Even before it came out I was trying to learn as much as possible. I’d seen some films that were shot on 5D – short and fictional – but not a feature length documentary.

Q Who are the DPs you look up to?

A [Shaoguang] I like Martin Ruhe and No Country for Old Men’s DP, Roger Deakins.

Q How was it shooting boxing with the 5D with shallow depth of focus? Surely that was incredibly hard?

A [Shaoguang] It was not an easy shoot – because of the shallow depth of field and because our subjects were constantly moving. Also, we knew this film was going to be seen on big screens so anything that was soft or out of focus would be very obvious.

Q Was there a lot of footage you couldn’t use?

A [Shaoguang] It wasn’t like a lot of things were totally out of focus – it would probably be that for a ten-second shot, maybe the first three or four were out of focus, but the last six were focused. Also, editing pace – in particular the fighting parts are pretty fast – meant you can accept change of focus and movement.

Q Was that frustrating? It must have been very different, for example, to shooting your previous doc Last Train Home on regular camcorders.

A [Shaoguang] It was a little frustrating at the beginning, but as a DP you’re supposed to know your camera and get used to it. That didn’t take long.

Official Clip – China Heavyweight – directed by Yung Chang from EyeSteelFilm Distribution on Vimeo.

Q What was your basic set-up?

A [Han Yi] We had a 24-70 f2.8 and 70-200 f2.8 and a 16-35 – which we didn’t use very often because sometimes we found the pictures too distorted. Then one 50mm prime lens – the director liked that very much because it gave you a ‘sense’. It’s pretty much like your eyes in terms of distance and feeling. One lens Shaoguang used most was the 24-70. We broke two lenses. As the producer I was very frustrated, because we didn’t have enough funding in that first year of shooting.

[Shaoguang] I was in the ring – we were filming two boxer sparring – and I was just too close. someone punched the other guy but instead of the punch landing on the other guy, it landed on the lens. It was a 16-35. I felt somehow the camera in my hand was lighter and something flew out – the lens was broken in half. We also used a Zacuto Z-finder. At the beginning we had a screen. We had a rig but it was a Chinese copy.

Q Most of the shooting was hand-held?

A [Shaoguang] 80% handheld, 20% tripods – for beauty shots.

Q Was it a style or a budget decision not to have jibs and dollies and so on?

A [Shaoguang] It’s more efficient for documentary – something happens; you don’t always have time to set up.

Q How much control did you have over subjects or did you just let everything happen?

A (Han Yi) Most of the time we just film whatever happens in front of camera. But sometimes we would try to create a space for the characters. For example if they were going to talk – we knew students were going to talk to the coach, but maybe we could make suggestions that they could do it somewhere else with better lighting, natural lighting. We could do that. But in terms of shooting fights you have no control whatsoever – you just have to follow the flow. And with their training we didn’t really have the authority to interrupt.

Q Who was making these decisions?

A [Han Yi] The director. In terms of lighting – We are not in that school of documentary where you have to film everything as it is in front of you. For example, if it’s too dark, we would try to light it. You have to allow the audience to at least see what’s going on. We always have an LED with us – a Litepanel. We’d use that or we would change the existing room lights from 25w bulbs to a 100w ones. In situations where we can make that decision we will. But most of times it happened too fast – there’s no time for any set-up.

Q Would you do anything differently if you could go back.

A [Shaoguang] I would use the C300 if I had a second chance – it’s a small camera, has better options for lenses, I have better experience of using it and it’s just better than the 5D. It has better sound too.

Q How did you cope with data?

A [Han Yi] The post was all done in Canada. In production we made the data as organized as possible.We have a label system – if it was today [July 9 2012] we’d mark it M07D09Y12 – all our files were labelled this way. Because we recorded sound separately, so at the end of each day the visuals needed to be synced with sounds. We did that after shooting-the director was very diligent. He’d want to see the stuff, if possible, every day. And we backed up the footage right away. But later, because the transcoding is too time-consuming, we had it done in post.

We had a Sound Devices 744 mixer with a Sennheiser 416 mic and 2 Sennheiser wireless mics – basically we needed another person. A soundman.

We made a little box ourselves with a light so that we could audio sync easier. I have a button and if I push it, it will light up. Then the camera will see the light and the sound person will tell him the number of the recording. It is not that complicated but does require good cooperation between the cameraman and the sound man.

[Shaoguang] I didn’t need to worry about the sound. That’s a big release for me as DP. Second, if you only use an on-camera mic you can only get one channel and sometimes we had three channels.

Q Did you just have one 5D mkII?

A [Han Yi] For most of the shoot, more than 90%, we had just one camera, the 5D. Wherever there is a fight, the fight had multiple cameras. For provincial fights we only had two: one 5D, one 7D. For the national fight and later the professional fight had two 5Ds, one 7D, one EX1 and one Sony F900 because we wanted to get different angles.

Q What’s the state of the documentary industry in China?

A [Han Yi] I don’t think we can call it an “industry”. There are a lot of independent documentary makers, but no support from the government, no distribution channels. Censorship is a big problem. So you see lots of subject matter is more about history, wildlife, arts. The audience here doesn’t have many choices other than the old-fashioned TV style – with the voice of god and the anchor telling you what it is instead of showing you. It doesn’t take long for them to make a judgement that documentary is boring compared to Hollywood films. Although we did see a few Chinese documentaries that travelled the world in the past years, they didn’t make it to the broadcasters or the majority of China’s ever-increasing cinemas. There are no distributors here for documentaries. The cinemas believe documentaries don’t make any box office so they refuse to show them or only give you bad time slots to prove you don’t make money.

The government should do more to support independent films and the support system is not there at the moment in China. We don’t have any funding from the government for documentaries. One good thing, though, was the launch of the CCTV (China’s state broadcaster) documentary channel in 2011. That did give these independent film-makers some hope that at least there’s a potential buyer there. In the past there was no buyer and no audience. So at least for a filmmaker your work can go somewhere instead of staying on a shelf at home.

There are also a few organizations supporting independent documentaries, such as Guangzhou Doc Festival and CNEX Foundation. They’re trying to teach local filmmakers how to produce or co-produce films with other people and bringing commissioning editors from around the world to the pitching forums.That’s a good way too, so people can learn how the documentary industry in Western countries works. It’s always about collaboration. But the pool of international money is shrinking because of the financial crisis and budget cuts. And the competition is fierce. We should try to look for alternatives to fund Chinese documentaries.

Q Can you tell us more about the budget?

A [Han Yi] We had a relatively big budget compared to other Chinese documentaries’. We had five people on the crew – the director; me, as producer/translator/coordinator/nanny; the DP; a sound person and a camera assistant. And the post was done in Canada.The funding was mainly from broadcasters around the world including ZDF, Channel 4, NHK , TV 5, the Movie Network and Movie Central from Canada; YLE; DR; and the Sundance Film Fund, and CNEX Foundation, a Beijing-based foundation for documentaries. One thing is that this film is the first official China -Canada treaty co-production, produced by Yuanfang Media in Beijing and Eyesteel Film in Canada. We got Canadian tax credits as well. That helped a lot.

Q How were you able to gain all that funding?

A [Han Yi] I think we were really lucky. The team has done two films before. The first came out in 2008 – Up the Yangtze. Then Last Train Home. Because both films have won over 40 awards internationally, this team has a track record in this industry, so I think there was trust. We had two Chinese producers and two Canadian producers who worked really hard to secure the funding, but I think the most important thing is that this team had proved it could deliver a good story with good production quality.

Q How do you feel about Western documentary crews coming in and doing stuff?

A [Han Yi] That’s a very good question. I think their perspective will be somewhat different from Chinese crews, definitely. We probably understand things better from the Chinese perspective. With China Heavyweight, the director was born and raised in Canada although he’s Chinese, so we have a lot of communication between me and him and crew and we’d offer our opinions sometimes. But it really depends on the subject and the point of view. Some documentaries made by foreign crews are really good.

[Shaoguang] Someone from Western and someone from Eastern culture will certainly have differences; maybe clashes. That’s one of charms of documentaries; they allow you to have your own opinion. You don’t all have to agree on certain things; maybe the exchange of these thoughts can help better understanding.

Q What did you enjoy most about the filming?

A [Han Yi] One thing he enjoyed – and something I enjoyed – was the relationship with the subjects. You just feel for them, especially when you’re filming a fight – and it’s heartbreaking when you see them fail. When we watched the last fight…we were in tears. They are not subjects any more; they’re part of your family. Even now we still have connection with the subject of Up The Yangtze, which we shot in 2006, and the family in Last Train Home. That’s something we treasure, as a team.

[Shaoguang] As a professional documentary maker you’re supposed to keep your distance from your subject – but when you get to know them and build up a relationship, that’s hard.

Q What’s next for you?

A [Shaoguang] For now I’m doing mostly commercial work – 70% of my time – including testing cameras for some of the companies. I am also doing underwater filming at the moment. I don’t really want to become just another DP. It’s something I’m interested in and having fun with.

[Han Yi] There are also a few projects we’re doing but they’re in very early stages. It won’t be as easy to raise funds as for the previous films. One is about a blind man with the ambition to travel the world solo and about his journey to forgive the abuse he went through when he was little and learn how to love.

Q Do you think you’ll work overseas in future?

A [Shaoguang] For documentary projects I’ll be mainly here in China – firstly, because of the language issue and also because with documentaries it’s all about your knowledge of a society besides the technical stuff. China is the society I understand best and where I can communicate best. Maybe I’d try to do commercial work elsewhere if opportunity allowed.

[Han Yi] I like to work in different environments and countries. I agree with Shaoguang that China is the society I understand and communicate with the best. But I’d like to explore more opportunities and now that I’m travelling back and forth between China and Canada I’m looking forward to opportunities to work in Canada too and other countries – maybe in Africa, or Latin America.

Q What advice would you have for aspiring documentary makers?

A [Shaoguang] As a DP you have to know the technical side. But that’s not the only thing. You have to observe; you have to understand and have good communication with your director and subjects. You have to learn from life and your mindset is more important. I wish I could do better in this regard! You have to be positive and relaxed through the whole process but in some moments you have to stay very hungry. That’s something I’m still learning.

You can now buy the DVD release of China Heavyweight on Amazon or rent it on demand at Vimeo.